- NWA Yesterday

- Posts

- You'll shoot your eye out, kid!

You'll shoot your eye out, kid!

The lasting impact of Daisy on Northwest Arkansas.

I want to tell you how one corporate decision made in 1950’s Michigan changed the life of a kid growing up in Rogers in the 2000s. It’s a story about…

A windmill company that couldn't sell windmills.

A two year old boy from Michigan.

And the world's largest BB gun.

Ready for a story?

A Windmill Company That Couldn't Sell Windmills

Daisy Airgun Museum

The story of Daisy Manufacturing was far from a bullseye start. In fact, it didn’t even begin with airguns.

In 1882, watchmaker Clarence Hamilton founded the Plymouth Iron Windmill Company in Michigan, betting on all-metal windmills while wood was still the industry standard.

The company struggled.

And by 1888, the company was one vote away from liquidation. In a last-ditch effort to keep the factory fires burning, Hamilton approached the board with an all-metal air rifle he’d designed.

When General Manager Lewis Cass Hough fired the prototype, he famously said, “Boy, that’s a daisy!”

The company started giving away the air gun with every windmill purchase. It was just a sort of marketing gimmick. But by 1895, they officially pivoted, abandoning windmills to focus entirely on the "Daisy BB Gun."

By the 1940s, Daisy was a household name, anchored by the Red Ryder BB gun—one of the most successful licensed products in American history and later inspiration for film history's most quotable scene: "You'll shoot your eye out, kid!"

But success brought growing pains. By the mid-1950s, Daisy was bursting at the seams, scattered across aging buildings in Plymouth. They needed room to grow.

So in 1958, they made a decision that would reshape both the company and an entire region: they moved everything to Rogers, Arkansas.

Trains began the journey south, loaded with parts, machinery, and inventory.

And, most importantly, people.

A Two-Year-Old Boy from Michigan

Daisy Airgun Museum

Daisy made an offer to key employees: come with us to Arkansas, and we'll help you relocate. Dozens of Michigan families took the leap, loading up their lives and driving 850 miles south to a place most of them had never seen.

Among them were Robert and Marcella Smith and their two-year-old son, David.

At the time, Northwest Arkansas was primarily agricultural. It was poultry farms and apple orchards, not factories. Rogers had just over 5,000 people.

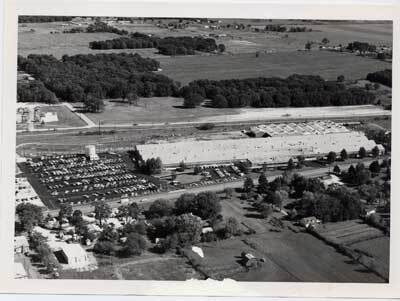

Daisy built a massive 250,000-square-foot facility and became Rogers' largest employer almost overnight, offering year-round industrial wages that catalyzed a shift from seasonal farm work to stable factory jobs.

The company's success did something revolutionary: it proved Northwest Arkansas could sustain major manufacturing. You could build a high-volume facility here, recruit and train a skilled workforce, and compete nationally. Other companies noticed. The infrastructure built for Daisy laid the groundwork for manufacturers like Bekaert and Glad to establish their own operations in Rogers in decades that followed.

Hundreds of workers like Robert Smith went to work each day to build airguns on a production floor that was quietly transforming the local economy. Meanwhile, their children like David headed off to schools, made friends, played sports.

By the time David graduated from Rogers High School as an All-State football player in the mid-1970s, Rogers had transformed from a town of 5,000 to a growing center of manufacturing and opportunity.

In 2003, Daisy moved its primary operations to Neosho, Missouri. It was a blow to Rogers and the end of a 45-year era.

That’s life I guess. Factories close, relocate, evolve. But the people they bring? At least, those who stay, who build, who invest in the next generation—those leave a lasting impact.

All those kids who moved here from Michigan grew up. Some moved away. Others went to university then came back home. One returned with a passion to serve his community as a teacher and coach.

David Smith spent over thirty years teaching and coaching at Rogers Public Schools. Earned a spot in the Mountie Hall of Fame. Became one of two coaches in Rogers history to win a state track title at Heritage and RHS.

He fell in love with a woman named Brenda on a blind date in September 1985. Engaged by December, married the following March. Raised two sons, Jacob and Jordan. Became an adored Papa to his grandchildren.

Funny isn’t it? One corporate decision in 1958 brought a two-year-old boy to Rogers.

Sixty-seven years later, that boy had impacted thousands of lives.

Including mine.

The World's Largest BB Gun

Daisy Airgun Museum

The world's largest BB gun leans against a brick building on Walnut Street in Downtown Rogers. A 25-foot monument that effectively says, "Daisy was here."

Some may think it’s a bit kitschy.

And to be fair, it’s a tad quirky.

I friggin’ love it.

It’s a reminder of the Daisy BB gun I got as a kid. Of shooting at squirrels off the back deck with my cousins. It’s a monument to childhood summers and questionable judgment.

But now, it’s taken on a whole new meaning.

I attended David Smith's funeral on December 27, 2025.

That's where I learned about his connection to Daisy, how his family had moved from Michigan in 1958, and that the Smiths became Rogers people because of a corporate relocation.

I knew David as a track coach from my days at Rogers Heritage High School. But even more so, I knew him as “Jacob’s dad.”

Jacob led my church small group in high school and became one of my closest mentors and friends. He invested time and energy into a kid who often didn't feel seen. Pushed me when I needed pushing, believed in me when I struggled to believe in myself. Made me think I could actually do something worthwhile with my life.

At the funeral, I sat shoulder to shoulder with a whole row of young men who Jacob had at one point invested in. All of us shaped by Jacob, all of us inadvertently connected to his dad David, all of us sitting in that church because his grandfather Robert Smith took a job at a BB gun factory in 1958.

It's strange to think that, in part, my entire knowing them depended on decisions made by executives in Michigan seventy years ago. Decisions driven by production costs and labor markets. Numbers on a spreadsheet that somehow led to one of the most important relationships of my life.

Community Outlives Corporate

Every day, people move to Northwest Arkansas for work, making the same calculation Robert Smith made in 1958. They load up U-Hauls in California, Texas, New York, Michigan. They buy houses, enroll their kids in school, look for churches, find their place.

Change is hard. Growth brings tension. We debate what it means to be "from here," who has the right to claim this place as “home.” The traffic gets worse. Housing costs climb. The culture shifts in ways that feel both exciting and unsettling.

But three generations from now, someone might sit at a funeral and thank God for the grandparents of their mentor or coach who took a leap of faith to move their family.

How many generations does it take to consider yourself a native? I don't know the answer. David Smith was born in Michigan but spent 67 of his 69 years in Rogers. His sons are native Arkansans by any measure. His grandchildren have roots here that go back to 1958, deeper than many families in this rapidly growing region.

But maybe being "native" isn't about bloodlines or how far back you can trace land ownership. Maybe it's about what you build, who you invest in, how you show up every day to make your community a little bit better. Coach Smith certainly did that.

He didn't just live here. He poured himself into this place.

Companies rise and fall. Factories shut down or move. But people? People build communities that outlast any corporate decision.

So, that giant BB gun on Walnut Street?

It’s not just a quirky monument to a factory that eventually left town. It's a reminder of all the invisible threads, the job offers, the family moves, and the two-year-old boys who grow up to shape thousands of lives.

Rest easy, Coach Smith. The legacy you built carries on.

Sources: